The roots of Brambly Hedge are stained with blood. While I, like most people, fondly remembered the charming little stories as a countryside idyll from early childhood, as I read them to my daughter a darker truth revealed itself in the corners of Jill Barklem’s bewitching illustrations. While the mice of the hedge –Poppy Eyebright, Mr. and Mrs. Apple, Dusty Dogwood, and the rest – spend their days gathering berries, singing songs, and getting into innocent mischief, a close reading of the texts shows that this is a world borne of steel and desperation. It is clear to me that the Brambly Hedge series is a continuation from the epic, war-torn world of Redwall.

The heirs of violence.

NOTE – I am not going to discuss Primrose in Charge or Wilfred to the Rescue here; they are not canon.

Brian Jacques’ Redwall books, as you should all know, tell tales of animals living in and around Redwall Abbey and the Mossflower Woods (and in further-flung parts of that world, as the series progresses). Like so many fantasy series, they’re set in a fictional version of England – the species that populate the books are almost all native to the UK, and the landscapes are pre-industrial but decidedly British. They are constantly violent, like Game of Thrones with Beatrix Potter’s characters. The main protagonists – badgers, hedgehogs, hares, and especially mice – are constantly under assault by rats, wildcats, and ferrets. All but the gentlest of characters fight and kill other creatures. It’s a more or less feudal society – Mossflower has abbots but no kings or gods; other species have kings and lords – with its own myths and folkways and values. I won’t go into them in depth – with the exception of the characters being animals, the Redwall books are not very different from any good fantasy series for young adults. I’ll just leave you with the knowledge that the last book ends with no sweeping societal resolution. The Abbey is saved from the latest marauders, to be sure, but there’s no reason to think that life in Mossflower won’t continue to be defined by the sword forever.

An ordinary day in Mossflower.

Fast forward from here to Brambly Hedge. On the surface, the mice of the hedge enjoy a delightful existence; everyone is friends, everyone revels in the turn of the seasons, everyone celebrates each other…all that they need to do is gather, prepare and eat delicious food together. Such, it seems, is life in the Hedge.

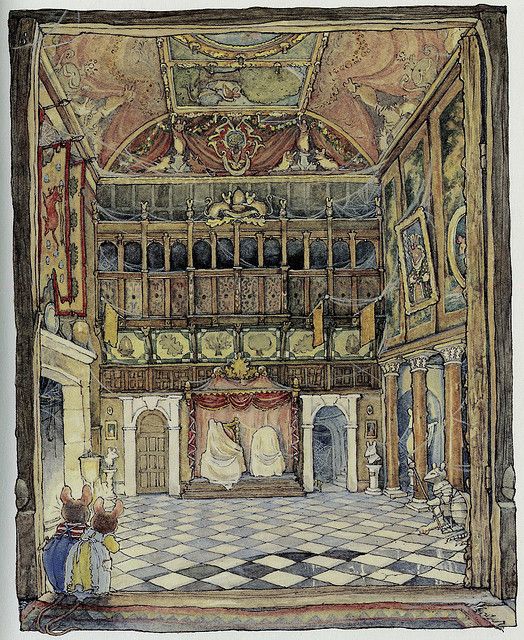

However. By the 850th reading of The Secret Staircase, you notice things. You notice that the Old Oak Palace, along with a variety of other places in and around Brambly Hedge, contains massive networks of secret or lost hallways and storerooms. Why are they hidden? By whom? FROM whom? When Wilfred and Primrose explore the further reaches of the Palace, they find suits of plate armor standing in the sumptuous ballrooms among paintings and tapestries…and thrones.

This place.

There’s more. In Sea Story, the mice voyage down to the coast in a dhow-like craft, clearly the work of sophisticated shipwrights. In The High Hills, Wilfred and Mr. Apple go on a difficult, dangerous mission into the mountains to deliver blankets to voles. In Winter Story, the mice show themselves to be adept at subnivean living despite apparently not having seen snow in many years. All of this raises many questions.

Consider the throne room. This room could not be the product of the subsistence-gathering economy we see depicted throughout the eight Brambly Hedge books. This room speaks of an elite class of mice, mice that had assembled the resources to import marble and commission self-glorifying artworks – and that commanded the military power to collect and protect those resources. The tapestry we can make out most completely indicates a starker, harder era in Brambly history – it is an unclad mouse (in the books the mice are clothed), with a spear, on a yellow field littered with what can only be arrowheads.

All of these are clues to the origins of Lord and Lady Woodmouse’s power in Hedge society. Their position of authority is not examined, let alone critiqued or challenged, in any of the books. While they appear to be benevolent and kind, and they allow their daughter to play with common children, there is no question about their social role. They live in a literal palace, and Lord Woodmouse presides over all public occasions….except spiritual occasions like weddings and christenings. For this they’re joined by Old Vole, who lives nearby.

What are we to make of all this? The clue is in the hedge. Hedgerows, in and of themselves, indicate major environmental change. The forests were destroyed somehow, and we see enough of the landscape – the map on the inside cover of the book is quite clear – to know that the trees are not growing back. What transformed the landscape, and with it the life of the mice? Fires, followed by the influx of some sort of browsing ungulate (aurochses, I would think – in real life, they only went extinct in the 17th century), seem like the likeliest mechanisms. Given that the evil characters in the Redwall books are almost always carnivores, the safest guess would be that at some point Mossflower was invaded by hawks, which hunted the rodents with fire – hawks actually do this – and then continued to burn in order to keep hunting grounds open and mice contained. While Redwall Abbey itself was made of sandstone and would not burn, the devastation of forest habitat and the way of life associated with it would have triggered a religious and political crisis in Mossflower.

Imagine. The fall of the woodland and the depredations of the raptors devastates Mossflower society. Whereas they’ve always been able to meet their enemies – rats, weasels – on the field of battle, the hawks really cannot be defeated. The sword of Martin is useless against air power. Traumatized mice stream into the Abbey from the countryside. In this sort of concentration, diseases run rampant through the community, and mice are forced to choose between dying of fever in the filthy, teeming Abbey, or in the talons of a hawk after foraging through the ashy wasteland that had been Mossflower. This pressure fissures the tolerant multi-species society depicted in the Redwall books, as badgers and hares retreat to Salamandastron, and shrews and hedgehogs, defended by their spines and venom, negotiate a separate peace with the hawks. The power of the abbots is broken – three die of fever in rapid succession, elevating a good-hearted but timid mouse who can provide neither defense nor sustenance nor even spiritual comfort. An archer-king rises, compelling his people to abandon the abbey for a new home. While their short bows are not enough to defeat the hawks, the mice manage to fight their way across open ground to a thick tangle of vegetation surrounding an ancient oak tree. Oaks can live for more than a thousand years; the Old Oak was probably alive in the days of Mattimeo. The holly and ivy and brambles grow over a spring, so here the mice have both a supply of water and a protection against fire. The blackberry thorns keep the hawks away. In Brambly Hedge the shattered mice build their life anew.

For the mice, there is one benefit of this societal collapse – it destroyed their ancient foes, the rats, snakes, and so on. The hawks ate weasels just as they took squirrels, and though they could not readily carry off adult foxes or wildcats, they were happy to eat the kits. The vermin gangs, which bitterly hated the hawks but lacked the social cohesion of the abbey animals, dissipated into factions and melted away. The only predator we hear about in the Brambly Hedge books is weasels, and then as a child’s passing fear – we never see them. This tells us that the predators who’d ravaged Mossflower for eons only remain as a sort of hedge boogeyman.

The survivors do not return to the abbey; in a few generations, it is forgotten. The archer-kings, having established themselves in the hedge, realize that with their limited resource base they will not be able to support their followers, or to retain power. They send out delegations, traveling under cover or by night, to re-establish trading networks between the hedge, the coast, and the mountains. The blackberries growing on the hedge are distilled into a cordial that travels well and fetches a high price from dune and alpine animals that lack access to such products. Note that we see blackberry punch as a social lubricant in Winter Story. On the coast, the mice learn how to improve their shipbuilding from the water shrews they meet there. For a time, the liquor trade supports the mouse aristocracy, and they are able to import plate armor that renders mice impervious to the hawks – heavy to lift, and impossible to eat. After many years, the hawks leave.

But the mice push the resource too hard. The blackberry crop collapses, and in the lean winter that follows, the mice of the hedge, already mulling over the socialist values they’ve learned about from the shrew union, look askance at the marble statues and oil paintings adorning the Oak Palace. A great council is held in the empty store stump. The current king, a mouse of vision and subtlety, makes a public show of humility by asking a vole to preside over the meeting. He sits amongst the common mice in the audience. The king asks the vole to begin the meeting with a prayer for prosperity and wisdom.

By doing this, the king set the locus of spiritual authority outside the hedge and curtails its reach while retaining and respecting the vestiges of Abbey-era tradition. He also removed the main challenge to his own power. Thus Old Vole (as all the vole-priests are called – it is forbidden for mice to speak their given names) blesses weddings and name days. This explains the offerings of blankets the hedge mice bring voles in The High Hills – the voles are a priestly class who do not interfere with the secular authority as long as their needs are supported.

At the meeting, the mice decide to turn inward and make the kingdom into a commonwealth, run so as to be self-sufficient, and trading only for items important to the community, like salt. The king voluntarily abdicates, retaining only the style “Lord Woodmouse,” a title that carries with it an echo of the forests that were once the hedge mice’ home. The move preserves not only the Woodmouse family’s social position but also their home in the Old Oak Palace. Without income from the cordial trade, it is too expensive to maintain the entire stately home, so the doors to the far-flung rooms are shut and largely forgotten. But old folkways persist – the tradition of naming females for flowers for instance. Matthias’ wife, remember, is named Cornflower. When young Primrose and Wilfred rediscover the dusty halls of the regal era, even her father, the 287th Lord Woodmouse, has only the faintest idea what his ancestors did or how his family came to live in the Old Oak Palace.